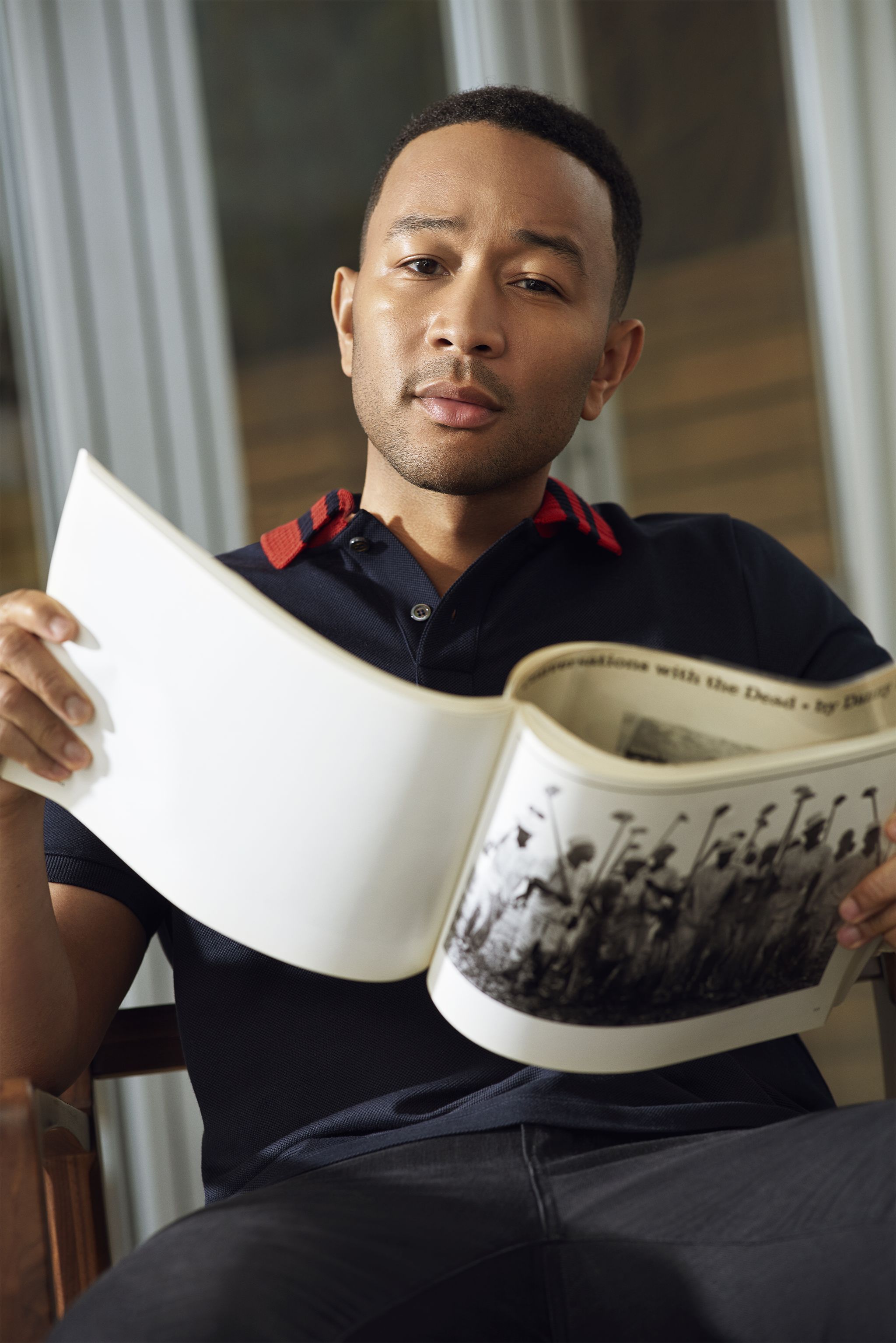

I listen to John Legend often. It’s not just because of his soulful voice, his insightful lyrics, his exciting ability to blend everything from gospel to pop to jazz to funk. It’s because, with all the work he does outside the recording studio—including his newest initiative, a fund that will seed businesses and nonprofits launched by formerly incarcerated would-be entrepreneurs—his music contains my own worries, my own disappointments, and my own hopes. In conversation, too, he’s as incisive, perceptive, passionate, and nuanced as his music would suggest. I’m fairly certain that, as an artist/activist/philanthropist, John has an impact on America that would hardly be improved by his taking public office. But I’m even more certain that he’s far more likely to one day be a senator than I am to ever score a record deal.

Cory Booker: Hey, John, it’s Cory.

John Legend: How are you doing, Senator?

CB: I’m doing all right. And please drop the title and call me Cory. How you holding up?

JL: I just got back from Europe, where I was preparing for my fall tour there, and we’re touring in the States this May and June.

CB: That’s great. One of the hardest things I did in 2015 was write a book, and I ended up on Spotify making this mix that I called the Legend Mix—it was 80 percent your songs. And more than you know, man, I would listen to that around the clock, just trying to motivate myself to get this book out of me. A lot of it, I think, was not just the music but knowing that you are a kindred spirit when it comes to a lot of issues I’m most passionate about.

JL: I’m glad that I could help inspire you, as you’re inspiring us by the work you’re doing.

CB: Thank you. You are honoring one of the greatest American traditions: the commitment for artists to be activists as well. During the civil rights movement you saw Joan Baez, Dick Gregory—so many people who showed a lot of courage, because whenever artists step out they risk their popularity. Is that something you worry about?

JL: Obviously, when you step out on anything that’s controversial, someone disagrees with you. And some people take that disagreement in stride and say, "You know, I don’t agree with you, but I like your music, so I’ll still buy it," or, "I’ll still come to your shows." Some people can’t separate the two and say, "If I disagree with you politically, you’re not going to make money off of me." And that’s just the price that we have to be willing to pay.

As you said, some of the greatest artists we’ve ever known have been willing to risk some social capital to try to improve the lives of other people. Nina Simone said it’s an artist’s duty to reflect upon the time in which we live. I don’t believe that every artist should do it, if they’re not mentally prepared, if they have not studied up on the subjects, if they’re not passionate about them. But don’t hold back if you are passionate about something. If you care about something, your fans want you to be authentic. I have a very successful career even though I’ve been very willing to speak up politically.

CB: Can you tell me where your conviction comes from? I read that as a kid you won an essay contest for a piece in which you talked about wanting to be an artist who gives back to his community.

JL: I read so much as a kid. My parents homeschooled us some years, and some years I was in private school, some years I was in public school. But no matter which school I was in, I was a reader. I loved reading about civil rights leaders, about presidents who did lasting things that made people’s lives better. I loved reading about leadership and people who made a difference. To me, living a significant life meant not just trying to make money but doing something to help somebody else, and doing something on as big a scale as I possibly could. I believed from a young age that that was part of what it meant to be an artist, and part of what it meant to live a significant life.

CB: One of my all-time favorite American artists was James Baldwin. He said that children are never good at listening to their elders, but they never fail to imitate them. Who helped shape your character?

JL: My family, who were at home but also at church. My grandfather was a pastor, my grandmother was a church organist, my mother was a choir director, and my dad was a deacon and taught Sunday school and played the drums at the church. So part of my ethic came from the Christian creed of caring about the poor, caring about your neighbor, the ideas of forgiveness and grace and redemption. I’m not very religious now, even though I keep all those lessons in my head. Other inspirations over the years have been artists who have used their art to make the world better. Stevie Wonder is one of those inspirations. Marvin Gaye is one of those inspirations. Nina Simone. Harry Belafonte, who is a friend and an inspiration. I’m friends with Bono, who has done so much great work over the years fighting AIDS and poverty around the world.

CB: Before we get into the details of your criminal justice work, I’ve observed that you’re very knowledgeable—you really seem to have done the work on complex issues—and you’re very humble in how you go about it. You go and listen to folks on criminal justice, whether it’s law enforcement people or people who are actually in prisons. Your attitude isn’t, Hey, I’m somebody here who is going to help you; you seem to want to learn and recognize their dignity, their value, knowing that you can benefit from it. You’re also fiercely pragmatic about what is actually working. How did you come to have this approach?

JL: My work-study job in school was at Upward Bound, which does educational programs for lower-income and first-generation kids who are aspiring to go to college. My first job out of college was at Boston Consulting Group, a major strategic consulting firm. One of the projects we did together was Management Leadership for Tomorrow, which is an organization run by Johnny Rice, the brother of Susan Rice. His organization works with minority kids, who are often not given the best positions in business and at business schools; it tries to improve their prospects by giving them training and mentoring and opportunities to succeed. At both of those organizations I learned the value of having a real plan and a real strategy, having goals that you are going to measure your progress against, and really being practical about what it means to change people’s lives.

CB: Okay, let’s dig into your criminal justice work. In 2013, when I was running for Senate, I wanted to talk about criminal justice reform wherever I campaigned. I’m very passionate about it. But I was surprised to learn that it’s not an issue that polls high. It’s not something that’s top of mind for most people. So, I’m curious, why are you so passionate about it?

JL: Part of it is having seen the effects on my own family and neighborhood, and overall in the larger black and brown communities around the country. Having so many people in prison at a time, having so many people with criminal records, has been really devastating, not just to people of color in America but especially to them. For people who aren’t interacting with the criminal justice system, there’s often this distance—they just kind of ignore it. They assume that the law is the law, and if someone breaks the law then they’ll get into trouble, and it’s kind of a fixed sentence, and that’s that. They don’t feel like it affects them, and they don’t feel they can do anything about it anyway.

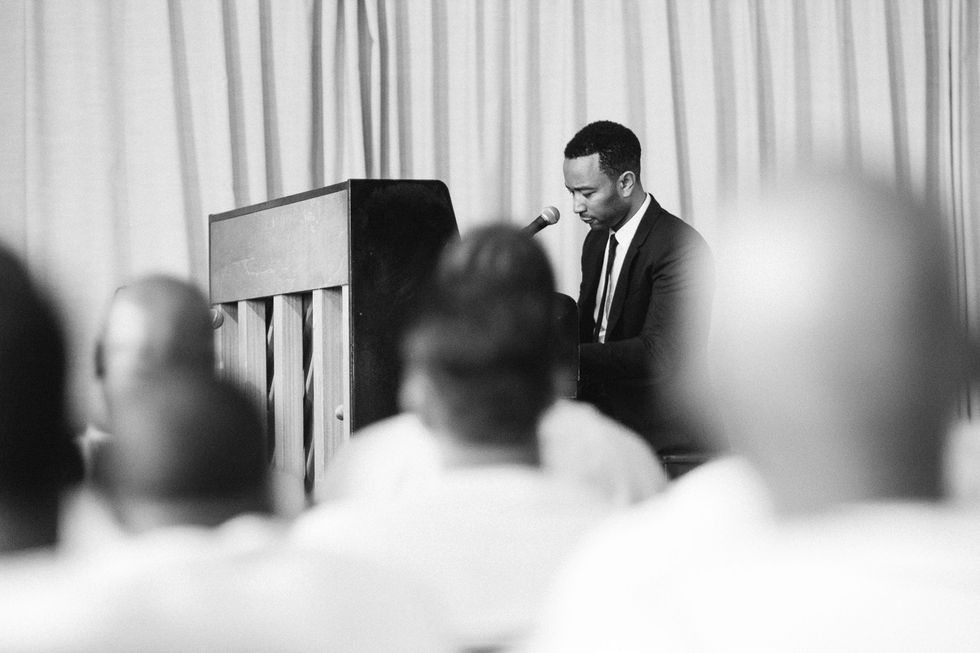

When I accepted the Oscar for “Glory,” for the film Selma, something that I wanted to highlight about the movement that encompassed Martin Luther King and other civil rights activists is that we are still dealing with issues of freedom and justice in -America in the 21st century. I specifically chose to talk about our mass incarceration problem, because if you want to talk about what is going on in America today that Dr. King would be concerned about, I think mass incarceration would be right near the top.

At that point I had also been reading people like Michelle Alexander and Bryan Stevenson, and I was instructing my team to put some more dollars behind it and start focusing some of our energy—almost all of which had been on education reform up to that point—on criminal justice reform. We started #FreeAmerica [a nonprofit awareness campaign]. We didn’t do it because we thought it was the most popular issue to talk about, but I’m in a position where I can help affect the conversation. You’re in a position where you can do that too, and both of us have chosen to do it. And I think people are talking about it more because of people like us, and people like Ava DuVernay, people like Jay Z doing the Kalief Browder documentary, the Black Lives Matter activists responding to specific incidents—all of us are helping to move these conversations to the forefront. I’ve seen real progress in the last few years. We’ve seen laws change, sheriffs change, and district attorneys change because of activism.

CB: I was on my feet when you used that moment when you won the Oscar to talk to the American public. I remember exactly the data point that you used—it got gasps.

JL: Yeah, the data point was that there are more black men under correctional control in America right now than there were under slavery in 1850. I believe I got that fact from Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow. That has been fact-checked and shown to be true. The other statement I made was that our country has the most incarcerated people in the world, which was also fact-checked and proven to be true. That should make us feel ashamed, because you think of all the countries that we consider to be repressive, to be unfree in so many ways. How can we say we’re more free if we’re locking up way more people than all those other countries?

As people like Ava DuVernay and Michelle Alexander have talked about, the way the criminal justice system has been used to control black bodies and brown bodies has some of its ancestry in the system of slavery. It’s right for us to think about them as related to each other, and important for us to look at some of the parallels of the system and think about how we fight to end mass incarceration, just like we fought to end slavery.

CB: The data point that I’ve heard you use is that America has about 4 to 5 percent of the globe’s population, but that 25 percent, or one in four, of the imprisoned people on planet Earth are here in the U.S.

JL: Yeah, it’s truly insane.

CB: Free America seems motivated to prick Americans’ moral core enough to make them move. Am I observing that correctly?

JL: Yeah. Part of it is really about changing hearts. We do that through storytelling. We have a documentary that we’re working on now called Walk with Me. We have scripted films. All of these things are meant to change the narrative, humanize folks who are involved in the criminal justice system, help people see that these folks are not dramatically different from those who don’t get caught up in the system. They’re human, they make mistakes; they’re often in situations where mistakes are exacerbated by the conditions in which they live. We are focusing on thinking about how to reinvest the money, resources, and societal energy we put into punishing and incarcerating people back into improving communities, giving people hope and opportunity before they ever get into trouble, and then giving those who have a record the opportunity to redeem themselves afterward.

CB: Here’s a quote from Free America’s literature: “Our goal is to restore incarceration rates back to their levels prior to the mass expansion of the prison and jail systems, and redirect savings to support concrete investments in education, rehabilitation, and reentry. In addition”—and this is a bold statement—“we support removing youth from all incarceration-type facilities.” I just want to put that in a global context. There are places like New Zealand that redirect the overwhelming majority of their kids from institutions, from courts, from prisons. So it’s not too far out of the mainstream of humanity.

JL: We are out of the mainstream of humanity with the way we do it now. We are radically punitive in America. We do really awful things to our young people, who shouldn’t even be in the same system as adults to begin with. We need to change the conversation so people realize that what we do now is radical. Reversing that wouldn’t be radical. It would be humane. The fact that we can try 14-, 15-, and 16-year-olds as adults is inhumane and ridiculous. The fact that Kalief Browder could sit in an adult prison as a juvenile for a backpack—he wasn’t even convicted of stealing it, he was just accused of stealing it—and just because he couldn’t pay the bail, he was sitting in jail for years. We lost his life because of it.

CB: We have had our prison population go up 500 percent since 1980, and we’re spending more than a trillion building prisons, incarcerating people, doing to children what other countries consider torture—things like putting them in juvenile solitary confinement, trying them as adults. You seem to be saying that we allow ourselves to do this by dehumanizing the people in this system.

JL: A part of it’s racism, to be clear. When it’s not your kid, and it doesn’t look like your kid, it’s easier to think the worst things about somebody. Part of it’s classism; you don’t comprehend the kind of situation these young people are growing up in, the neighborhoods they’re growing up in. You don’t understand the factors that contribute to them straying off the path. You assume they must be evil. You assume they must be irredeemable. In reality, the fact that kids make it out alive without getting in trouble is sometimes a miracle.

CB: You and I both know that it’s actually a fact that young kids in tough, inner-city environments are not breaking drug laws at rates different from kids on college campuses or kids in wealthy neighborhoods.

JL: That’s true. The rich kids are using drugs, and they are not getting arrested. Then we see the opioid crisis in certain communities, and people are saying, “You know what? We need to do something to help these kids and not lock them up.” I just want people to have the same level of empathy for black and brown kids in the ’hood that they would have for a rural kid growing up in West Virginia who is dealing with a painkiller addiction. These addiction crises are hitting a lot of communities, so let’s have empathy for all of them and see all of them as people who could be our own kids.

CB: You and I both have a devotion to Bryan Stevenson. You’ve quoted him before saying, “None of us should be judged entirely by the worst thing that we’ve done.” You really are a champion of this idea for even violent -criminals. A lot of people are too shy to say this. They just want to talk about the nonviolent drug users.

JL: That’s easy to get sympathy for. You have to realize that when people commit a violent act, there are a lot of factors that go into that. And the definition of violence is pretty wide. It can go from the worst things, like murder and rape, to getting into a fight. All of that is considered violent. We have to have a little bit more nuance when we talk about what it means to be locked up for a violent offense.

CB: That point is so important. There are people who do nothing violent, who might just be driving a car, who can get convicted for a violent offense.

JL: Such as if you’re an accessory, if you’re involved in any way. A lot of times, if these people don’t have good representation, they’ll cop a plea to something just because they were scared that if they got the maximum they would be locked up for a really long time. They’ll cop a plea to something, a felony, when they probably shouldn’t even have been charged with that in the first place.

CB: Like a Ta-Nehisi Coates or a James Baldwin, you have this capacity to talk unflinchingly about racism in our society. What are the challenges of talking about race right now?

JL: People feel defensive around the subject of racism, and they shut down, because they feel like they may say the wrong thing and you’ll think less of them. But we have to deal with the fact that these issues have a real impact on people’s lives. There’s a real impact when they’re not getting called back after they’ve applied for a job because they have the wrong name. And there’s a real impact when a police officer assumes a person to be more of a threat because of the color of the person’s skin. We are dealing with these things every day, and the only way we are going to fix them is if we confront them, listen to one another, and empathize with one another’s concerns. We can’t worry more about being accused of being racist than we do about actually fixing the racism problem.

CB: You’re launching Unlocked Futures, a fund that will provide grants and training for formerly incarcerated people to launch businesses. Can you explain how you decided to do this?

JL: We need to reinvest our resources from punitive things to actions that are restorative and edifying for the community. Part of that is investing in our young people before they ever get in trouble. But also, there is a huge population who have criminal records, and 60 percent of them, a year after being released, still don’t have jobs. We know that if they’re not working in the legitimate economy, then a lot of times they are going to be working in the illegitimate economy, and they’ll end up back in prison. So one of the things we have been focused on is developing ways to encourage entrepreneurship in those communities, so that these people have an opportunity to start their own businesses, start their own nonprofits, and start contributing to the community instead of being dependent on another employer to hire them. We are doing this project, which is a social venture fund, with New Profit and Bank of America, and its purpose is investing in business and nonprofit ideas for people who have been incarcerated.

CB: I know you are a family man. You and your amazing wife Chrissy became parents a year ago to a daughter, Luna. How has that played into your thoughts about making a lasting contribution?

JL: I think that having a kid automatically makes you think about your legacy and your own mortality. Another aspect for us was realizing how challenging it is to have a kid, even for somebody rich, famous, and successful and with the kind of staff that we have. Even we have challenges. It's stressful, and it requires a lot of energy and time and a lot of resources. I think it has informed my politics in a lot of ways, because I know that our daughter is going to have everything she will need, but there are so many mothers and fathers and children out there who don't have it. And part of my mission and politics is to make sure that more people have what they need to give their kids a chance to succeed in life.

Styled by Nicoletta Santoro; Grooming by Naivasha Johnson for Exclusive Artists using Chanel Sublimage. Set design by Philipp Haemmerle. Tailoring by Yasmine Oezelli for Lars Nord. Produced by Wanted Media.

This story originally appeared in the June/July 2017 issue of Town & Country.